Where the forests are alive, and the Kingdoms are awakening

A Gambian Fable – November 2020

It’s interesting how we block ourselves. Why we suddenly refuse to ‘let go’ of our comfort zones; of the belief structures firmly entrenched in our minds and the patterns it likes to keep hold of – even though the magic and potential of the new that’s presenting itself is so utterly delicious.

Most of the time, we prefer being caged. We can be addicted to our suffering – because, hell, suffering in itself can be even more delicious. The dramas of life are intoxicating; addictive; supremely fucking entertaining. Where would we be without them? All that sweet, sweet sorrow! That luminous regret. The heart-pounding rage.

Yummmmmm. There’s something perversely sexy about binding ourselves in chains.

And I was reminded of this – again – when I dug out this piece last week that I’d written on my trip to The Gambia roughly 14 years ago.

I’d just turned thirty.

For someone who’d always classed herself as a freedom-loving flippertijibet, my own masochistic love of being bound in such make-believe structures has always been a thing.

And reading this piece again, I saw how my patterns of resistance and control were operating even then.

Well. Of course they were. I just wasn’t conscious of them yet.

Let’s all just face it, though. How addicted are we to our patterns that are keeping us anchored in the limiting experiences we’re having?

And which also keep us in the illusion of ‘safety’; keep us trapped inside our roles; trapped inside nonsensical societal constructs that are devoid of true power and meaning; that keep us tightly wedged inside our boxes of beliefs on how things ‘should’ be… And which stop us, of course, from truly letting go… into the unknown. Into the abyss.

Ask yourselves this, though:

What wonders – and fun – might be waiting for you there??

***

I was in love with Tom when I went to The Gambia. He called me as I was poking about in the bookstore at Heathrow. I’d better go, I said, after we’d spoken for a while, I’d better go or I’ll miss the plane, I’ll be home sooner than he thinks if that happens. Don’t leave, came his reply. Come back. The parks here in summer are lovely.

Erm. But it was only April. And anyway, I wanted to get away, not just for the sun; I wanted to relax and I wanted to read and I wanted to sleep and most of all, I wanted to be on my own. I was running away, I admit, I was running away from interaction, because interaction required energy, and at that point, I had none to give. I was sick of being sucked into the bubble, sucked into having to play the game. Someone talks, you respond. Someone pulls out a chair, you sit.

You need to be alone sometimes. So I said goodbye to Tom and hung up.

Things that I knew about The Gambia thus far:

- It’s only six hours from the UK.

- The time difference is zilch. This equates to no jet-lag.

- It’s hot.

- It’s coming up to low season in April, so there are no direct flights.

As a result of this latter, I had to connect in Brussels. It was here, as I waited to board the second plane, that I met him: Demba, a body of tall black perfect muscle, was joining the connection from Germany, where he’d lived for eleven years, and where he currently taught jembay drumming in Hamburg schools. He’d fascinated his pupils, been prodded and poked by them. “Chocolate?” they’d asked him, upon which he’d ran his fingers smoothly up his arm and explained, “yes, but not chocolate to eat. Chocolate you can touch, gently.”

He was taking a week off to visit his family.

I, meanwhile, was clutching my book. I, aloof and British, guarded it jealously in my right hand, my index finger already wedged between the cover and the first page, ready to dive into the words at the first opportunity, headlong and mindful. I thought I’d managed to get shot of him when we finally boarded, but as soon as we took off, there he was again, having left his seat and come to join me next to mine. Irked wasn’t the word; I kept wondering what he wanted…what he wanted really – not to mention that in the hour I’d been in his company, I really hadn’t seen anything worth smiling so much about. “I am from The Gambia – the Smiling Coast of Africa,” Demba informed me, by way of explanation.

I wondered if The Smiling Coast of Africa – or indeed The Smiling Coast of anywhere – was the right place for me to go and lose myself in a big vat of fuck all. Demba remained sitting next to me, grinning, tapping a rhythm onto the seat in front. I play the drums too, actually. But it wasn’t the right kind of drumming, I was told, not if you play using sticks – you’re too far away from the source of your creation – and like everything else in life, you need to get closer to the Source and become a part of it. Beating the drums with your hands, on the skin, is the best, and most primitive way.

You connect

I was unconvinced; besides, I didn’t want to be. So Demba rolled up his shirt and flexed his muscles. Ten minutes later, he was clutching on to the seat in front of him, all drumming lectures forgotten as he squealed and prayed whilst the plane lurched and fell down through the sky. He turned and looked at me aghast as I sat there, my book whipped open in a flash. “It’s gonna be ok”, I told him, and seconds later – when it was – he said to me, in all honesty and awe, “what kind of heart do you have?”

I had no idea… A confused one? From the short time it took from touching down on tarmac to emerging from the terminal building into the blazing African sun, I was dragged through an avalanche of emotions – first jealousy as Demba laughed with a beautiful woman on the shuttle bus, all smooth skin and bootylicious in a short lemon dress, then gratitude as he ushered me through the swarms of travellers trying to get through passport control.

“I told you,” he chuckled as he greeted the airport staff, the officials, the police, his ‘brothers and sisters’…“we are in Africa now,” – a thought which provoked first excitement then pure alarm when we both got pulled over by Customs.

“Are you with him?” one of the officials barked. “Yes,” Demba growled – making me wonder if he had drugs, and if this had been some kind of elaborate game-plan all the way from Brussels. Would I be implicated? End up in jail?

“I met him on the plane,” I squeaked, just before we were let go, and found ourselves scrambling into a taxi, whereupon we were driven to Demba’s mother’s house – a little house in a large yard shaded by mango trees, under which a very beautiful young girl stood with her sister, who sat nursing her baby boy, and whose little dog Afri chased me round mercilessly, snapping my ankles till I was ushered into Demba’s jeep.

He said something aggressively to the beautiful girl before we rolled off, reggae pulsing full blast out the speakers as we drove through the alleyways, chased by wide-eyed children in colourful dresses, and then by swarthy young boys near the Craft Market, who were all screaming Demba, Demba like he was some kind of benefactor; a demi-god. He handed them mobile phones brought over from Germany through the window, even though he was still angry about the fact that, despite having taken his niece (the beautiful young girl) to Europe so that she might aspire to more in life, she’d been using her own gifted phone to facilitate meeting and fucking round with the local men.

There are equal opportunities for both sexes now in this country, Demba is telling me; schooling for girls is free; the vice president is a woman. But this doesn’t mean everyone’s grateful for it. Already, they’re taking it for granted, and wanting to follow their instincts instead…”It’s human nature”, he adds, “and that will never change, no matter where you’ve come from. We’re all the same deep down. Beneath the colour of our skins, the blood inside each of us flows red. But you have to work. You have to make your way in the world. That’s what I always knew. I was never going to make do with an old white woman just to get ahead in life.”

I don’t know what to say, so I comment on the flowers. The flowers are everywhere, here in Demba’s mother’s garden. “I planted them all in her yard, too,” Demba tells me, “but she tore them all down, she felt too enclosed.” And then, “I have land, other land, that no-one knows about, but I will tell you and only you.”

I liked The Gambia. I liked to walk along the beach, with my feet in the waves. I liked the fruitshakes at Funky Banana’s stall, and the effortless way that a young boy called Charley beat out rhythms with an older man on the jembays in a nearby cafe. Their pulses met his voice in such an expression of unity that it seemed odd to suppose that before that point these sounds had never existed. Charley said he knew Demba.

At the Monkey Park with a man called Abdul, I got in trouble with the park ranger for bringing in peanuts. Abdul got in trouble with me for being too explicit. Sometimes he has dreams, he wakes up in the middle of the night, shaken… “I produce..” he told me, his sentence tailing off.

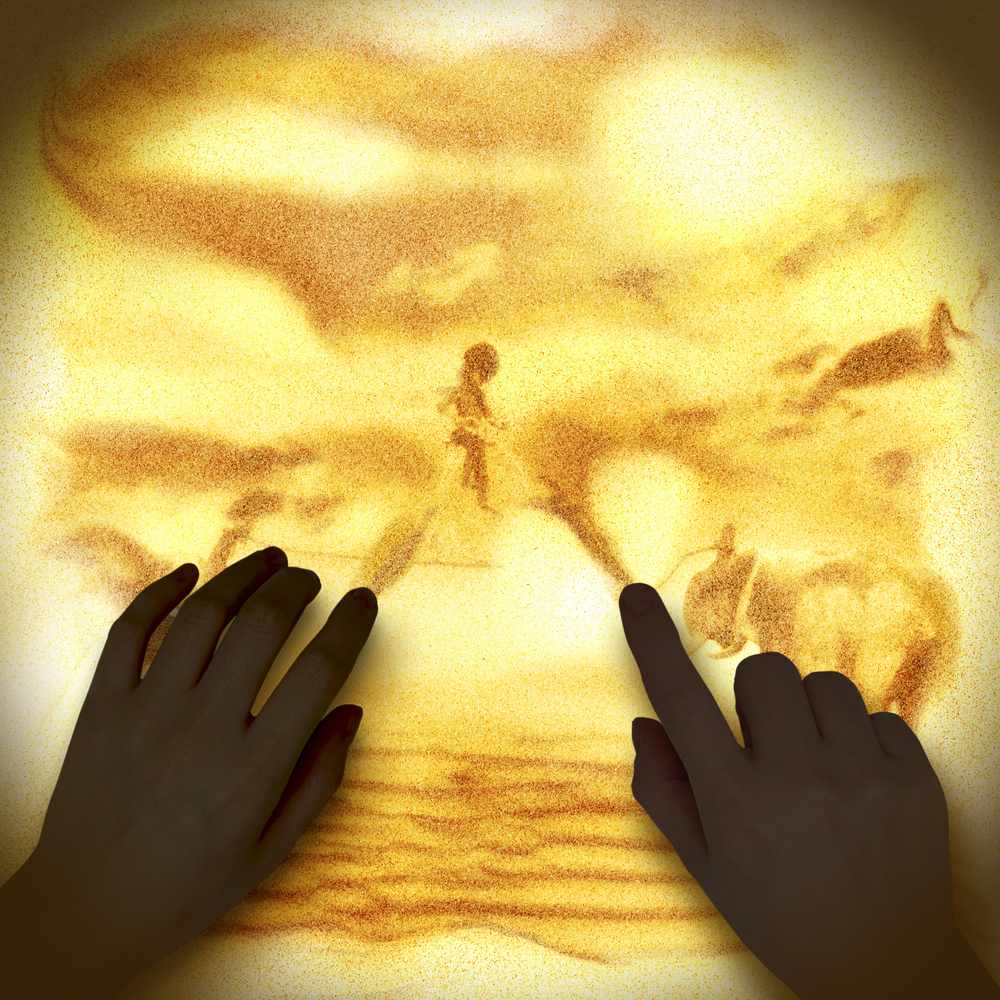

I suggested I hook him up with Nima, a striking maid at the hotel, but Abdul clearly wasn’t interested. He wanted an English girl. “You want a visa”, I clarified, and he didn’t deny it. He offered me a joint and asked me for a 600 dalasi for a bag of rice. I decided he could sell me a sandpainting for 400 instead. Now the tourist season was almost over, it would be hard for them to survive. It’s a poor country; peanuts are their only export. They rely on tourism, on people who love the beauty of their country. “The Gambia,” Abdul says, “is the Smiling Coast of Africa”.

“If that’s the case,” I ask him, “then why do you want to leave?”

They think Europe is paradise

This is what Demba tells me one evening. The sun is almost setting and we’re sitting on the beach, each with a bottle of coke and a jembay drum. It’s what Ann told me, too – the English woman who works in the restaurant at my hotel. She’s in her mid-fifties, and she upped and left after her divorce in England, and promptly met her Gambian man, a member of the Jula tribe.

Her boyfriend’s mother doesn’t understand that Ann isn’t rich – which in turn causes problems in her relationship. The old lady speaks no English, but that’s not the problem; it’s not the language – it’s the collision of two different worlds. They know how much the airfare is and can’t believe we have so much money – in the same way as Ann’s grandkids can’t believe that Gambian children could possibly be content with playing with an empty tin of sardines on a string, up and down the street, up and down. “People only see what they want to see”, she explains.

“I was like that myself”, I tell her, “in India way back when I was nineteen. I taught English in a school in Madurai, and shared a room with 16 kids. I helped them with their English as they counselled me through the shock of being in a third world country.”

I was young; I thought the world revolved around me. I still think about all that today, if I’m honest. I could have been nicer to those kids.

After the sun sets, Demba and I stop off at the Monkey Cafe. He tells me he had married a German girl and moved to Germany, then – after many years – had started drumming in the squares: with other drummers; with dancers. Soon he was teaching in schools. “Drumming is a way for children, especially those who find difficulty in learning, to find focus. Afterwards, they’re so happy. Physical exertion stills the mind. Each extreme creates the opposite effect, which in turn creates perfect balance. The whole universe is about balance. It’s why the earth is like it is: round, perfect, spinning like a ball in space.”

We drink coffee and I watch as he peels a mango with a sharp knife. Everywhere there are old white ladies holding hands with young, lithe black men. I spot Abdul, hanging out with some friends. I wave. “Is that the guy you said that knows me?” asks Demba.

“No, that’s Abdul.”

“Who?”

“The guy that knows you is called Charley.”

“Where did you meet all these guys?”

“Yesterday, on the beach.”

Demba thinks for a minute. “Have you ever had sex with a black man?”

I put my arm next to his and pick up the knife and go to cut ourselves. “I thought you said we’re all the same?”

Demba bursts out laughing. “You’re so smart it kills me.”

The next day he takes me to the sacred Kachikally Crocodile Pool in Bacau. We listen to the three same Jah Cure songs over and over again…repeat, rewind. Repeat, rewind. The crocodile pool is said to aid fertility in women (but only, I surmise, in those who favour the prospect of procreation over their own survival, seeing as you have to bathe with ‘vegetarian’ crocodiles). The tamest croc is called Charlie and quite famous; either that or drugged, which, these days, I suppose, is pretty much synonymous with fame anyway.

A huge tree dominates the middle of the ground – the circumcision tree – where thousands of women from the Jula tribe have been subjected to these rites for centuries. Even today, between 70-80% of Gambian women have been circumcised. I can’t get my head round it, and Demba is thoughtful. He asks me about having sex with him again, which annoys me for the rest of the day, and from this point on I refuse to crack a smile, no matter how many renditions of Jah Cure’s What Will It Take he treats me to back in the jeep.

He knows all about Tom; I’d told him from the very first night when he cooked me dinner in his flat and showed me his bed which “we could cuddle on later, if you wanted.” He knows all about him, this boy I love – even though I haven’t actually thought about him since I got here. But who cares? What business is it of his anyway?

I don’t stop for a fruitshake with the Funky Banana man after my evening walk, I just go straight to my room and read on the veranda. But something is happening on the beach; I can hear drumming over the crashes of the ocean and the din of the crickets. The beats are furious and frenzied, but underneath it all I sense the stillness and peace that I’ve always seemed to crave.

When you drum, Demba’s voice appears in my head, you must focus, you forget about the pointless worries of the world. You focus on the rhythm like a heartbeat, like the ocean waves; everything is cyclical, repetitive, like the laugh that comes out of your belly that sends the blood pumping round your body and back to your heart…everything is cyclical, round, perfect, like the earth, spinning in space.

After that, something changes in me and I chill the fuck out. Demba takes me to the nearby towns of Serrakunda and Banjul – bustling market towns full of blistering heat, smells and noise, and where I’m almost tempted to buy another sand-painting from a woman who asks me which part of London I live in, then laughs when I tell her Angel, and starts going on about Essex Road and the number 38 bus. I almost buy it, but then I remember Abdul and decide to go back to see him. By now, I know that a bag of rice does indeed cost 600 dalasi, and I also know that Nima (and all other hotel cleaners) only earn a basic rate of 480 dalasi a month, plus food and travel, which, altogether, barely scrapes a tenner.

“Isn’t it awful”, remarks Lesley, Steve’s wife, who’s in the pool with me one afternoon. She tells me about when she visited a school and had a child virtually hanging off every finger. One kept stroking the white skin on her forearm. “They don’t have anything we’re accustomed to.”

“But they’re happy,” chips in Steve. They’re from Bolton. It’s their first time here. They normally go to the States. “The Americans love us, don’t they?” Lesley breathes. “I don’t know why, I don’t think we’re particularly special.”

“It’s the accent,” Steve remarks, a bit more abruptly this time, like he’d like his wife to shut up.

I’d like a lot of things, really

I’d like it if The Gambia didn’t have to rely so much on tourism, and I’d like it if the West wasn’t so completely idealised, especially with the likes of Del Perma-Tan the hotel manager strutting around like Top Cat, winking at me and teasing me for dallying with a Gambian, then throwing his hands up and saying “I am from Barcelona, I know nothing,” when I ask him about his own bloody dallying. His wife and kids are in Lanzarote. He doesn’t see them often. He likes it here because white, older men are revered, which probably means he can go to clubs and not feel like a dick. Of course, the whole of this tiny country would be just one big tourist hell if Del had anything to do with it. He complains about the Gambians trying to sell their wares on the beach and annoying his hotel guests, and doesn’t know why they’d choose to do that than work for him in the hospitality industry.

When I complain to Demba, he shrugs and tells me, “it’s politics, what can you do? Stand up and they’ll kill you.”

I find Abdul and tell him I’d like another sand-painting. He tells me he’d like me to take a picture of him on my mobile phone, so I can blow it up and put it on the wall of my burlesque supper club in London and advertise his booty to any English woman who fancies a bit of chocolate. “Even old women”, he instructs me. Now that season is almost over, he’s going to leave the beach and go to the farms where he will pick fruit. I’d like him to realise that this is a hundred thousand times better than living with a geriatric in Putney Bridge. I’d like him to realise how special his country is, and I’d like him to know how much I’ve enjoyed my time here.

I’d also like not to have to go home, please. I say goodbye to Ann, who’s tearfully broken up with her Gambian man, and Nima. Demba takes me to the airport and gives me a jembe drum to take back with me, and a giraffe carved by his father. Finally, on the plane, I’m alone to read, but it’s difficult to read if you’re crying, and that’s all I do. All the way to Brussels.

Of course, in accordance with my flighty and fickle moon in Gemini, it doesn’t take me long to forget.

Demba doesn’t, though. Demba calls me most days after my return, until after a while, it gets too much and I stop answering. He sometimes leaves messages on my voicemail that consist solely of Jah Cure songs and nothing else.

For over a year, I don’t return any of his calls.

Until now.

As I’m writing this article, the memories flood back, and I pick up the phone. I dial his number and he answers. We talk. We talk some more and we laugh. Connecting feels good. We discuss music, and dancing, and drumming, and we plan to hook up at the reggae festival in Germany this July. When I hang up, finally, I feel ashamed that I’ve left it so long, and I don’t even understand why. And as I’m confronting all this, I’m suddenly struck by my doubts, my lack of faith – and by the resolute strength with which I still seek to resist.

Comments